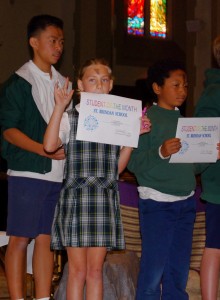

My mom and my daughter, Esther, in June 2012.

I wrote this piece in December 2012; two weeks after my mother died. It has taken this long for me to shine it up for public consumption. The heart is ready when the heart is ready…

Those of you that know me well know I didn’t have a great relationship with my mother. It was fraught with strife from the start (if what I was told was true) and continued through most of my adult life. Of course I don’t remember much before the age of six, but from that point I had the perception that my mother didn’t like me too well, that I was difficult, that my conception was, for her, an unhappy accident, and I came along just at the wrong time. If not for me, so the folklore goes, my mother would’ve traveled more, and lived her dreams. If not for me, she would’ve gotten her PhD and really made something of her life.

If not for me.

These kinds of myths, when imparted to a young child whether by word or glance or silence, persist, loom and grow larger as years pass and, at least for me, they became the foundation of a life fraught with a sense of worthlessness, which I came often to experience as paralyzing anxiety. This manifested in many ways: fear of flying, the ocean, taking tests, getting sick, auditioning, stepping on stage, and the ever pervasive “nameless dreads” – the irrational sense that something bad is coming, and coming right soon.

It feels like I’ve worked a lifetime at ridding myself of these demons, and for the most part I guess I have. I started seeing therapists when I was 7 years old. I stuttered pretty badly at the time, and my father was wise enough in the late 1960’s to understand this was likely an emotional issue, not one of speech mechanics. So, he took me to the school psychologist, also known as the “speech therapist.” I’m still incredulous that they had such a person on staff at a public elementary school in 1969. The next occasion I had to see a therapist was almost a decade later, around the time my parents divorced; then again in my mid twenties when I just couldn’t shake the panic attacks, cigarettes, cocaine, or bad-boy men-friends; and yet again in my mid thirties as a result of self-inflicted emotional trauma caused by my own infidelity during my first marriage. Worthlessness takes on many forms, and I’ve worn lots of camouflage over the years.

In the year 2000, I married Tim Klassen. With Tim came a sense of calm and long-sought stability (though it’s WAY more complicated than that) and, 3 years down the road, our greatest treasure: Esther. Now motherhood, as all mothers know, changes everything. Once you have a child of your own, you never see your own mother in quite the same way. And so it was that a light went on when Esther was born. I realized, Good Lord in Heaven, that my own mother is a human being. Who knew? My parents’ prohibitions, once thought equivalent to those of a jailhouse warden, began to seem quite rational and, truth be told, too permissive. Now I understood that my mom and dad had no idea what they were doing. While they appeared all knowing and all powerful, they were just doing what they thought best at the time. And while my father was busy saving the world one soul at a time, I imagine my mother was reading Dr. Spock blindfolded, crouched and shaking in the back of her bedroom closet.

Even as I have struggled to maintain a career in the 21st century and struggled to keep some culturally acceptable sense of a “personal identity” separate from my identity as a mother, I have NEVER struggled to love my daughter. That scenario is just not within the realm of possibility. And so it is that I’ve come to rethink the folklore of my childhood. Given my own experience as a mother, it seems likely that loving one’s children kinda goes without saying. So, is it not possible, logical then, that even in my mother’s struggle for identity and her desire to live her own dreams, she also loved me? Maybe even as fiercely as I love Esther? I think so. No. I know so. And I think, again based on my membership in the motherhood club, my own misguided belief that she didn’t love me broke her heart. I remember a few occasions when she tried with great desperation to explain her love for me, but it was all mixed up and awkward, rolled up in her ambivalence about career and marriage. It was covered so thick in Gloria Steinem, pop psychology, and Me-Generation rhetoric it turned my stomach, and I would have none of it. It took another 25 years and having a child of my own to understand the terrifying truth she was trying to express; something I, in my stubborn naïveté, have just barely come to accept: once you have children, you give up your dreams in deference to theirs – at least for a time, but maybe forever. It depends upon your kid, and it’s a risk you take. And I would add another somewhat controversial layer to it: A mother gives up her dreams in deference to her children’s, and that’s the way it’s supposed to be.

Knowledge of this truth has not kept me from pursuit of the illusory Brass Ring in my voice acting career, nor has it kept me from lone excursions to far away lands in pursuit of an ever-elusive peaceful state of mind, of lessons in how to let go of worry for the future, regret for the past and (at the risk of sounding just as entrenched in modern day Me-Generation bullshit rhetoric as my mother did in the early 1970’s) of learning to “be in the moment.” Why else, my friends, would I attempt to surf in Costa Rica with a bunch of 22-year-olds or balance myself in Bakasana (crow pose) at the age of 50? I’m a jokester about my own narcissism rooted in my parents’, but now that I’ve crested the great mountain of life and am staring down its descent, my desire to be in the moment has shifted focus. Lately, what I have wanted is to be fully present, not with myself, not with God even, but with the people I love right here, right now; my friends, my family, and especially my daughter. When I’m with Esther, I want to be with Esther, not focused on the dinner I “should” be making or the audition I should be recording. I want her to know I am right here with her doing homework from 1×1 to 12×12 and every word problem in between. I want to be with her on the swings and climbing the tree, not on the sidelines on my iPhone checking Facebook. It’s an on-going problem of mine, this not being “present,” and I’ve missed out on stuff I don’t want to miss out on anymore.

As Providence would have it, I did not miss out on what has turned out to be one of the most pivotal experiences of my life. Two weeks ago, my mother died. Her rather sudden decline over the last few months took us all by surprise, as my siblings and I were just coming to terms with having moved her to a residential care home where she would have round-the-clock oversight – necessary due to the deepening of her dementia. It was not easy for us to get to her, as I live 3 hours away by car and both my siblings live out of state. Nonetheless, we were all able to be with her at some point in her last weeks on this earth. Most of the time she knew who we were and was able to respond in kind when we told her we loved her.

After 4 weeks convalescing in hospital from an infection, she had been home only a few days before she was taken to the hospital again. This time she had suffered a few small strokes that sent her into a rapid decline. With the good counsel and care of the hospital social worker, we decided it was time to adhere to my mother’s advanced care directive, stop all heroic measures and bring her under hospice care. I asked the hospice nurse to be frank with me about how long she thought my mom might live and, God bless her, she was. Not months by any stretch. Not to Christmas. Maybe days, maybe a week. That was on a Wednesday. I planned on coming to see her that coming Friday, the 30th of November, and to stay a few days.

I drove to San Luis Obispo County and checked into my hotel, the Kon Tiki in Pismo Beach, before heading 10 miles further north to my mom’s. The ocean was roaring to the West and clouds were threatening rain ahead. I drove in the dark to Los Osos and arrived to see her at 6 pm. Ross, her caregiver, took me back to her room. I pulled up a chair next to her, reached for her hand under the sheet and fixed my eyes on her. The air in the room was warm and thick. The only sounds were the rain outside the window and the whoosh of her oxygen machine. The room was peaceful and expectant, womblike. She was sleeping, and while her breathing was shorter than usual, it was steady and calm. I didn’t want to wake her, so I kept my eyes fixed on her and said nothing. Her skin, my god, her skin. It was still flawless with nary a wrinkle, even at 82. My mother never went in the sun. She wore the silliest hats and goofiest sunglasses when I was a kid, keeping herself protected all year long from the California sunshine she sought as a young wife and mother in her 20’s, escaping what she perceived as the drudgery of life in the small town Midwest. I remember we’d go to Disneyland in the high heat of August and she’d tell us girls to put on long-sleeved sweaters, so as not to let the sun burn our skin. My sister and I, who would slather ourselves in baby oil in the midday sun every July, thought she was crazy. Ya. Crazy like a porcelain goddess.

After sitting with her for about 45 minutes, I looked at my watch and remembered that I hadn’t eaten anything since 10 am. I squeezed her hand just a little and whispered that I was going to get something to eat and would be back in an hour. As I let go, she opened her eyes. I took it as a sign, a signal for me to stay. So I did.

I searched the Internet on my phone for hymns of her youth and favorite scripture (there are times to praise the internet, it turns out) and began to focus my vigil. As I read and sang, and as her eyes once again closed, I realize how much of those hymns and pieces of scripture I knew by heart… And in knowing, I was able to keep my eyes focused on my mother. I was looking at … no, seeing… so intently my mother’s skin that when I began to notice a shift in her coloring, I thought my eyes were going wonky. Her skin was becoming translucent and I could see the tiniest, most delicate capillaries on her forehead. Her bone structure was amazing. She glowed. How can that be? How does one glow in such a state? I kept blinking to make sure I was keeping her in focus, and began to realize that she was dying before my eyes. The blood was leaving her face. Her breath became shallow, inhales less frequent. But my god, even as life was leaving her body, her beauty was palpable.

I had arrived at 6 pm that Friday. I sang and kept vigil until 8:02 pm when she took her last breath. It was not days, it was not weeks. She’d had only hours left. And I was present for them. Along with the hours spent birthing my child, these were two of the most privileged hours of my life. Within the span of them, I got to encourage my mother to Heaven, while every resentment, everything bitter, every failure between us drifted away. Vanished. Like they never existed. And it was nothing I did. It was the last and most treasured gift my mother gave me. By her willingness to die in my presence, she confirmed that she trusted me, that she loved me, that I was worthy of being present at her birth into eternity.

I did not call in the nurse for a good 15 minutes. I sat alone with my mother’s body and took in the last moments of her life. I felt in some odd way that I had witnessed a miracle, and even now I find it hard to articulate. I mean, what is so miraculous about death? It’s pretty pedestrian, really, and inevitable for us all. I didn’t see her spirit hover or ascend or see anything I thought to be supernatural. But I was struck again by how beautiful she was. I wanted very much to share this experience with my siblings who had wished so much to be by her side with me. So, as odd as it sounds, I took a picture of my mother in a last, feeble attempt to capture the moment, to capture the beauty I saw as she left this realm.

It wasn’t until the next day that I looked at that picture. And what I saw was as plain as day: my dead mother. A shadow of herself. No life. No translucence. Just a strange emptiness. It was not easy to see, and for a moment I was deflated. But in the next moment I grasped, finally, that what I had been working so hard to experience over the last few years had come to pass. The moment my mother died, I had been fully present. I was in the moment when it mattered most. With her, and nowhere else. And by being in the moment, I saw her.

I saw her sweetness.

I saw her innocence.

I saw her vulnerability.

I. Saw. Her.

And she was beautiful.

For an experience as emotional as this one was, I shed very few tears over the next few days and had little to say. I was mostly in a daze and out of my body, like I was hovering over the tumultuous Central Coast ocean, yet at peace. I imagined that this was kind of what Mary Magdelene (my patron Saint) must have felt when she saw Jesus in the garden that First Easter Morning. Miracles do that to you, I think. Leave you speechless…

And so it is, I have found, that even in death there are gifts to be received. Some would say it was a gift to my mother that I was by her side when she died. Maybe so, but I think I got the greater gift. My childhood folklore was dismantled and, irony of ironies, it was my mother who set me free from its tyranny. I don’t know exactly how that happened, so I’m choosing to call it a miracle, and leave the mystery intact. I have no desire to explain it away, only to embrace it, and hopefully, when the moment comes, offer the gift to Esther.

15 Comments | In: Short Stories | | #